The

land that Maria Campbell wanted

It

would be interesting to go back in time and meet Maria Campbell.

There are some indications that she was a bit of a character, and as

the daughter of a Scottish father and aboriginal mother in the early

nineteenth century, she would have experienced first hand the meeting

of the two very different cultures. As it is, what we do know about

her is that she wanted a sizable chunk of the property her father

left when he died.

Her

father, Archibald Campbell was convicted in Glasgow, Scotland. He

arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1804 as part of the group led by

Lieutenant Governor David Collins, and worked as a ferryman on the

River Derwent for a number of years.

The

name of Maria's mother isn't recorded but she may have been mentioned

in Henry Rice’s diary in 1820. On an expedition up the east coast,

he recorded that "we came to the Main Ocean to a place call'd

the Stoney Boat Harbour, where we buried Campbell's black woman."

The

first reference to Maria herself appears to be in 1818 when the Rev

Knopwood baptised Marie Campbell, an eight year old native girl.

She would have been about ten when the aboriginal woman was buried at

Stoney Boat Harbour. We know that Maria didn't learn to write because

she was later to sign her name by making her mark with an "x",

but conceivably she could have been taught to read.

In

1823, when Maria was about thirteen, her father married Jean or Jane

Jarvis or McWilliams.

Her new stepmother had at least seven children prior to being

convicted in Glasgow and transported to Van Diemen’s Land.

A few years after her father’s marriage, Maria would have met one

of them, Margaret McWilliams, who was transported for forgery.

She was about a year older than Maria. In 1828, when they were both

living in Collins Street in Hobart, there is a reference to a one

year old Helen Campbell. Helen may have been from the same household,

in which case she presumably would have been another step sister for

Maria.

Two more of Jean Jarvis’ daughters were later transported for

forgery,

and in time, both of her sons also turned up in Hobart.

Archibald

Campbell's career took a different turn in 1828 when he was granted a

publican's licence for the 'Highlander' in Macquarie Street in

Hobart.

Maria was now about eighteen and quite likely, she would have lived

and worked at the Highlander when it started trading.

Then,

nine months after he had been given a licence for the Highlander,

Maria’s father died.

During

the next few years we get an inkling of what Maria’s stepmother was

like. Jane Campbell destroyed the will in which her husband had left

some of his property to Maria and her stepsister Margaret,

and assumed control of her husband’s business interests.

Notwithstanding that she signed her name by making an ‘x’ on the

marriage certificate, Jane Campbell advertised the lease of a ferry

service,

bought a small property near the Highlander,

and for a while held the publican’s licence at the Highlander.

There

are several letters written to the authorities in Jane Campbell’s

name. One was addressed to the Lieutenant Governor after the Surveyor

General denied that she had any claim on a house and garden which she

believed had been allocated to her husband in Bellerive. The matter

was settled by allocating her another allotment nearby.

She was less successful in her efforts to stop a neighbour blocking a

laneway next to the Highlander public house and taking soil from her

property. An emotional and probably ill-advised letter to the

Surveyor General has this statement from Jane Campbell;

I

cannot patiently endure any further encroachments, Indeed I cannot

account for what reasons Mr Roberts Now attempts it, except it is,

the circumstance of my being A lone woman without A male protector,

and his desires to avail himself of the opportunity of annoying me.

Maria’s

stepsister Margaret McWilliams married George Scrimger,

a whaler, who a little later, was living near the Highlander.

The Scrimgers seem to have accepted Jane Campbell’s appropriation

of her husband’s estate because George Scrimger was the first

licensee of the Highlander after Archibald Campbell died, and after

Jane Campbell held the licence for a few years, he again took it on.

It

is less easy to trace what Maria was doing after her father died. We

catch a glimpse of her in 1831 when the Black War was in its final

stages. An uncertain future would have been facing any of her birth

mother's relatives who were still alive and so Maria would have had

few reasons to try to join them.

In

1831, she was couch surfing between the Red Cow Inn and the home of

Mrs Free, both in Clarence Plains and about a mile apart. Maria was a

witness in a case brought against the licensee of the Red Cow Inn,

and was described in the newspaper as "a very intelligent female

of 20 years of age". The newspaper went on to add that;

The

Court expressed a strong interest for this young woman, who appeared

to be cast on the world without protection of any kind. It was said

that her father had died, leaving her some property which had been

withheld from her, and it appeared to the Court and professional

gentlemen present, that her's was a case calling upon the Local

Government to instruct its legal officers to step forward and afford

their protection to her rights and claims.

Just

what the crown legal offices or Maria did immediately following these

observations didn’t come to light in a cursory search of the

archives, but a couple of years after the court case and not long

after her stepmother died,

Maria applied for the deeds to a farm that her father had bought in

Cambridge opposite Midway Point. About thirty acres in size, it was

the base for a ferry service to Sorrell, in fact this was the same

ferry service that her stepmother had previously advertised for

lease.

Maria may have also, at this time, applied for the title to the 100

acres (or rather 153 acres after it was surveyed again) that her

father had been granted on the Droughty Point peninsula in Clarence

Plains. It was later advertised as part of the standard process to

give anyone who opposed the grant the opportunity to state their

case.

The

following year in 1834, five years after his death, the Supreme Court

finally considered who should inherit Archibald Campbell’s estate.

At the request of the Attorney General, the Court accepted a copy of

his will which had been kept in a solicitor's office, and granted

probate. The beneficiaries of this will were his wife, Margaret

Scrimger nee McWilliams and Maria herself. As Jane Campbell had died

intestate, her share would now go to her eldest son, John McWilliams.

The will had a proviso that if either of the daughters strayed from

the path of virtue, their share would be forfeited and divided

amongst the other women.

The

family was to claim that Archibald Campbell held an interest in at

least five properties. There was the land in Bellerive that Jane

Campbell wrote to the Lieutenant Governor about. There were two

allotments in Hobart; the Highlander being located on one of them

and the two farms to the east of Hobart that Maria had applied for.

It

isn’t surprising that dividing up the estate led to a number of

disputes. By now, trust between the parties was probably in short

supply, but two years after the grant of probate, a written agreement

was endorsed by all the beneficiaries of the will. It set out that

the estate would be transferred to two trustees. Maria would be

allocated the thirty acres at Cambridge (opposite Midway Point) and

receive the associated rents and profits. The remainder of Archibald

Campbell's property, (and if Maria died childless, also the property

at Cambridge) would go to the Scrimgers who would settle with John

McWilliams.

The

Cambridge property today as seen from the causeway leading to Midway

Point.

The

role of the trustees seems to have been limited. They didn’t

subsequently apply for titles to the properties, and presumably they

seem to have little to do with the management of the properties

because it was agreed that the parties would take possession of the

properties in accordance with the agreement.

The

role of the trustees seems to have been limited. They didn’t

subsequently apply for titles to the properties, and presumably they

seem to have little to do with the management of the properties

because it was agreed that the parties would take possession of the

properties in accordance with the agreement.

Maria

took steps to sell her property at Cambridge, but the sale does not

appear to have been finalised. The authorities subsequently started

processing the claim for deeds to the property that she had made four

years earlier, and after her death, her step-family sold it to

another buyer.

Maria’s

next move showed that she did not understand, or did not want to

understand, the significance and/or the content of the agreement with

the Scrimgers and John McWilliams. When the 153 acres on the Droughty

Point peninsula was advertised for auction on a second occasion,

there was a public warning in the newspaper from Maria.

CAUTION

TO

ALL Persons not to purchase a piece of land situated at Clarence

Plains as described for sale in the Courier of the 24th inst., to be

sold by W.T. Macmichael on the 2nd Dec. next, as I, Maria Campbell

being the legatee to the late Archibald Campbell - the present vendor

having no legal claim.

MARIA

CAMPBELL

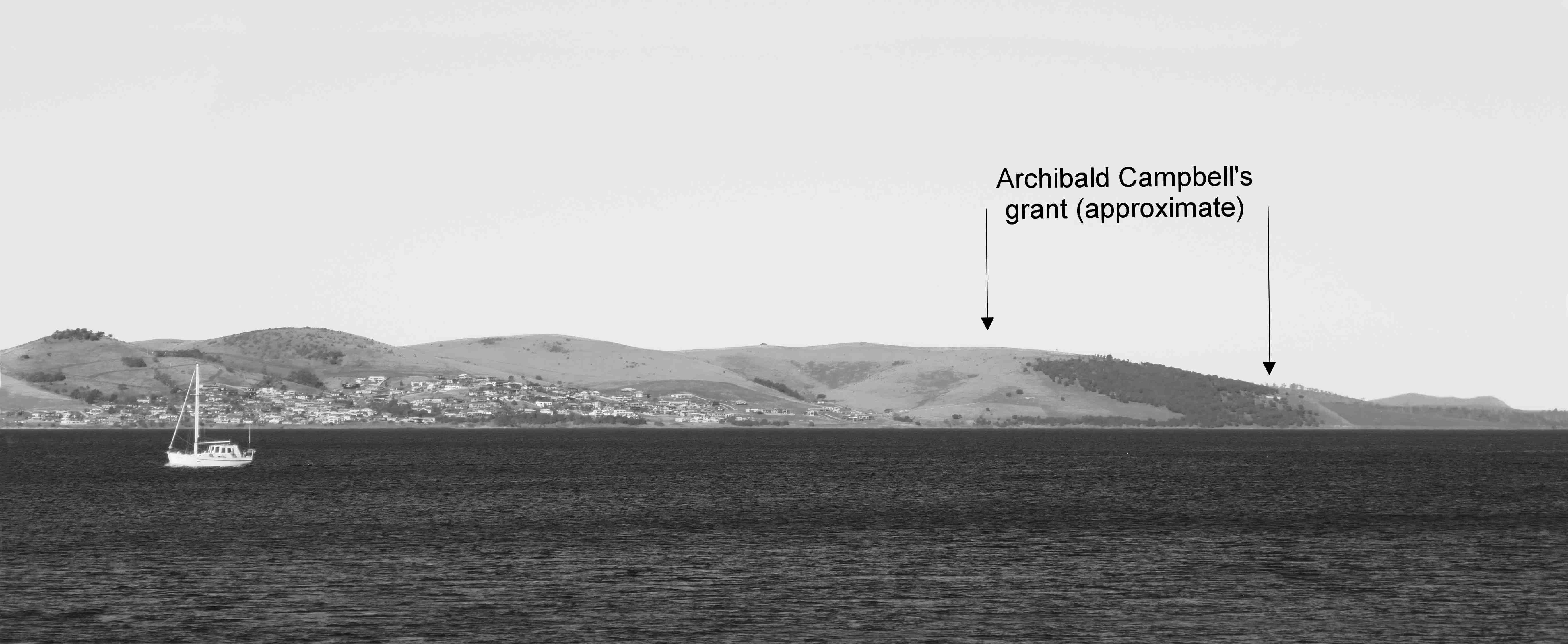

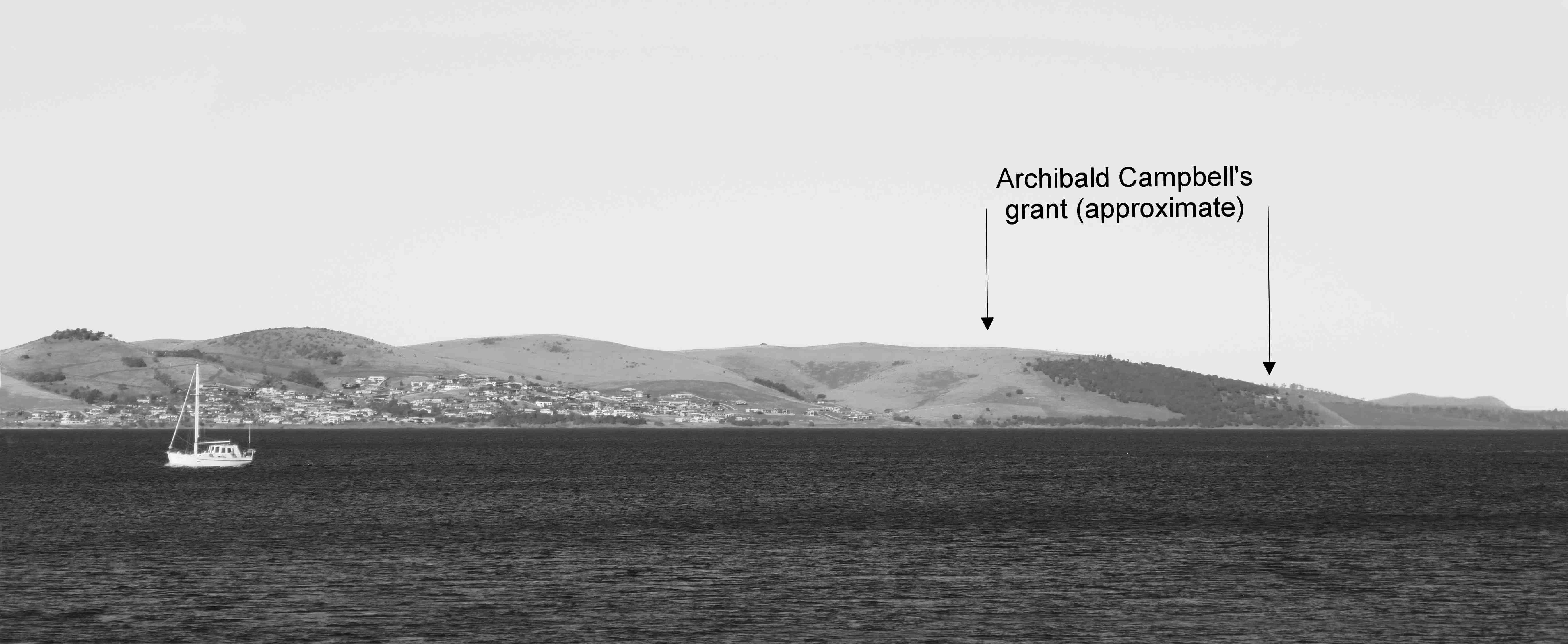

View

of the Droughty Point peninsula from the Hobart wharves

These

words of Maria's seem to be the last ones that have been captured

within the surviving records. Maria did not publicly challenge the

advertised sale of the Macquarie Street property.

Nor did she dispute the claim for the title of the Droughty Point

land by the new owner when it was sold the following year, even

though the hearing of any disputes was part of the process for

granting titles.

Perhaps her supporters didn’t think that a challenge could succeed

or perhaps the long and painful illness that preceded her death was

already taking hold.

These

words of Maria's seem to be the last ones that have been captured

within the surviving records. Maria did not publicly challenge the

advertised sale of the Macquarie Street property.

Nor did she dispute the claim for the title of the Droughty Point

land by the new owner when it was sold the following year, even

though the hearing of any disputes was part of the process for

granting titles.

Perhaps her supporters didn’t think that a challenge could succeed

or perhaps the long and painful illness that preceded her death was

already taking hold.

Maria

died in 1838, nine years after the death of her father. In that

period, she had gained control of one of his properties, but if the

final newspaper notice is anything to go by, she considered that she

was entitled to more.

There

was evidently still some connection with her stepmother’s family

because one of the younger stepsisters was present when she died.

Someone took the trouble to place a notice about her death in two of

the local papers, and one ended by saying that "Her loss was

deeply regretted and sincerely felt was all who knew her.”

It

was never going to be easy for a dark skinned woman with limited

education to live in a community where racism and male chauvinism

were commonplace, and where it was often assumed that the victim

would do their own prosecution and detective work. That Maria was

able to elicit support and have her case presented in court and in

the newspaper surely says something about her, and it has left us

with a partial record of her short life.

An

earlier version of this article was printed in Tasmanian Ancestry Vol

39 no 3 Dec 2018.

The

role of the trustees seems to have been limited. They didn’t

subsequently apply for titles to the properties, and presumably they

seem to have little to do with the management of the properties

because it was agreed that the parties would take possession of the

properties in accordance with the agreement.28

The

role of the trustees seems to have been limited. They didn’t

subsequently apply for titles to the properties, and presumably they

seem to have little to do with the management of the properties

because it was agreed that the parties would take possession of the

properties in accordance with the agreement.28

These

words of Maria's seem to be the last ones that have been captured

within the surviving records. Maria did not publicly challenge the

advertised sale of the Macquarie Street property.

These

words of Maria's seem to be the last ones that have been captured

within the surviving records. Maria did not publicly challenge the

advertised sale of the Macquarie Street property.